The expansion of Kusum Yojana 2.0 has revived interest among farmers and landowners across India who are exploring whether solar farms on barren land can generate steady monthly income.

While government-backed solar schemes under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) offer new opportunities, experts caution that earnings such as ₹50,000 per month depend on capacity, tariffs and financing conditions.

Understanding Kusum Yojana 2.0 and Its Policy Framework

India launched the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) in 2019 to promote solar energy use in agriculture. The scheme is administered by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE).

The programme has three components:

- Component A: Installation of decentralised grid-connected solar power plants, typically up to 2 megawatts (MW), on barren or agricultural land.

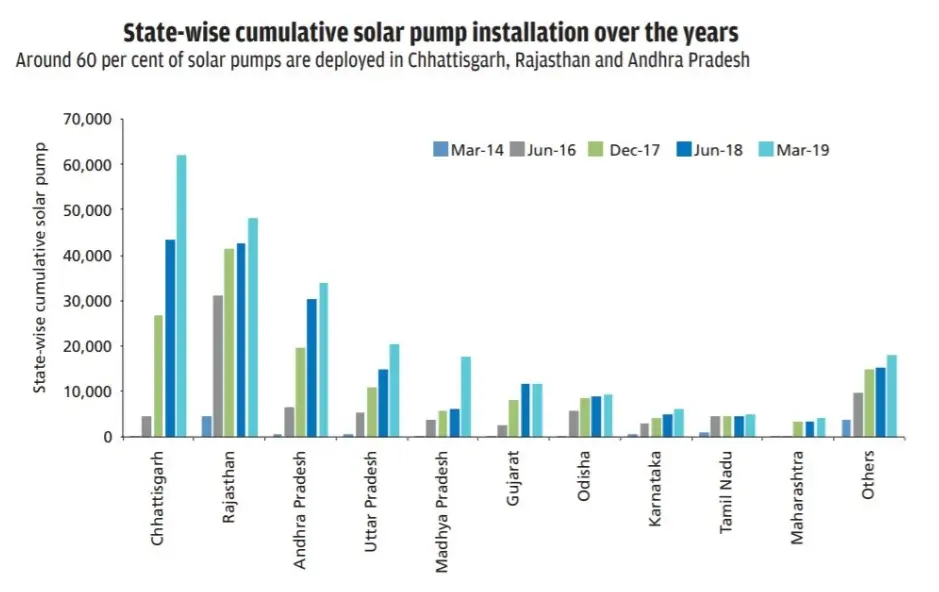

- Component B: Deployment of standalone solar pumps to replace diesel pumps.

- Component C: Solarisation of grid-connected agricultural pumps.

Government documents published by the MNRE state that Component A allows farmers, cooperatives, panchayats and Farmer Producer Organisations to set up solar plants and sell electricity to local distribution companies (DISCOMs) under long-term agreements.

The term “Kusum Yojana 2.0” is commonly used in policy discussions and media coverage to describe the extended implementation phase and refinements aimed at improving uptake and financial viability.

An MNRE official said during a recent briefing that the government aims to “strengthen decentralised solar generation and improve rural income security.”

Can Farmers Earn ₹50,000 Per Month?

The claim that Kusum Yojana 2.0 guarantees ₹50,000 per month is not officially stated in government documents. However, income at or above that level may be possible under certain conditions.

How Income Is Generated

Under Component A, a farmer or entity installs a solar plant and sells generated power to a DISCOM at a tariff discovered through competitive bidding or determined by regulators.

Revenue depends on:

- Installed capacity (for example, 1 MW or 2 MW).

- Annual electricity generation, influenced by solar irradiation.

- Tariff per kilowatt-hour (kWh).

- Operation and maintenance costs.

- Debt servicing if financed through loans.

According to data from the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) and various state tenders, average solar generation in India ranges from 1,400 to 1,700 kWh per kilowatt annually, depending on region.

If a 1 MW plant generates approximately 1.5 million kWh annually and the tariff averages ₹3 to ₹3.5 per kWh, gross annual revenue could reach between ₹45 lakh and ₹52 lakh before expenses. After deducting operational and financing costs, net monthly income may vary significantly.

“Returns depend heavily on capital structure and land ownership,” said an energy analyst at CRISIL Ratings. “Projects without heavy debt burden may achieve higher net income.”

Financing and Subsidy Structure

The financial model under Kusum Yojana 2.0 typically involves central and state subsidies combined with institutional loans.

According to MNRE guidelines:

- The central government provides financial assistance.

- State governments may add supplementary support.

- Beneficiaries contribute a portion of project cost.

Banks and financial institutions provide loans for remaining capital requirements.

However, experts note that debt servicing reduces net earnings in the initial years. Interest rate movements can also affect profitability. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has highlighted renewable energy as a priority sector for lending, but credit assessment standards remain rigorous.

The Role of DISCOMs and Payment Security

Income stability under Kusum Yojana 2.0 depends on the financial health of state DISCOMs. According to the Power Finance Corporation (PFC), overdue payments from DISCOMs to power producers have been a recurring issue in several states.

Delayed payments may affect cash flow for solar developers. The government has introduced reform-linked funding to improve DISCOM financial discipline. “Payment security mechanisms are critical for investor confidence,” said a researcher at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR).

Land Use and Barren Land Potential

A key appeal of Kusum Yojana 2.0 lies in the productive use of barren or low-yield land. India has significant stretches of arid and semi-arid terrain, particularly in Rajasthan, Gujarat and parts of Maharashtra. Installing solar panels on such land can provide income without reducing food production.

The MNRE has stated that decentralised plants reduce transmission losses and strengthen rural grids. However, experts also highlight environmental considerations, including habitat impact and land rights clarity.

Grid Integration and Technical Constraints

Solar generation is variable and peaks during daylight hours. The Central Electricity Authority (CEA) has emphasised the importance of grid planning and storage integration.

Increased decentralised generation under Kusum Yojana 2.0 may reduce pressure on agricultural feeders, but it requires upgraded infrastructure.

Energy storage remains costly, though prices are declining globally, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). “Decentralised solar can stabilise rural supply if managed properly,” said an official from the International Solar Alliance (ISA).

Risks and Ground Realities

While Kusum Yojana 2.0 presents income opportunities, risks remain:

- Variability in sunlight and seasonal output.

- Fluctuating module prices.

- Land acquisition disputes.

- Regulatory changes at state level.

- Delays in approvals and grid connectivity.

Experts advise potential participants to conduct feasibility assessments before investing. “Farmers must evaluate financial projections carefully and avoid overestimating income,” said an energy finance consultant based in Delhi.

Related Links

Agrivoltaics: Grow High-Value Crops Under Solar Panels; Doubling Farmers’ Income.

Iron-Air Battery: 100 Hours of Backup! 10 Times Cheaper and Safer Than Lithium.

Broader Economic Impact

Kusum Yojana 2.0 aligns with India’s larger renewable energy ambitions, including achieving 500 gigawatts of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030. Decentralised solar supports rural employment, reduces diesel consumption and enhances energy security.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), distributed renewable generation plays a critical role in expanding clean energy access in emerging economies. The scheme also supports India’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Kusum Yojana 2.0 offers a structured opportunity for farmers and landowners to generate income from solar energy, particularly on barren land. While earnings of ₹50,000 per month are possible under favourable capacity and tariff conditions, they are not guaranteed.

Financial viability depends on careful planning, responsible borrowing and reliable power purchase agreements. For rural India, the scheme represents both an economic opportunity and a policy experiment in decentralised energy transformation.