India’s Modi’s Solar Vision vs. Utility Reality push for mass rooftop solar adoption, championed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is facing structural challenges that go beyond policy intent.

While subsidies and ambitious targets have energised the sector, loan bottlenecks, cautious utilities, grid limitations and regulatory inconsistencies are slowing the pace of installations, raising questions about how quickly India can meet its clean energy commitments.

A Bold Rooftop Vision

When the Government of India launched the Pradhan Mantri Surya Ghar: Muft Bijli Yojana in 2024, it set out an ambitious goal: solarise up to 10 million households and provide free electricity up to a specified limit per month.

The scheme, backed by an outlay exceeding ₹75,000 crore, offers central subsidies to residential consumers installing rooftop solar systems. It is a core component of India’s plan to reach 500 gigawatts (GW) of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030.

Officials have described rooftop solar as critical for decentralised energy generation, reduced transmission losses and consumer empowerment. In public addresses, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has framed rooftop solar as a step towards “energy independence” at the household level.

Yet, despite policy clarity and public messaging, implementation has proved more complex.

The Modi’s Solar Vision vs. Utility Reality Financing Gap

Banks’ Risk Perception

One of the most persistent obstacles to scaling rooftop solar remains access to affordable credit. Although subsidies lower installation costs, most households must still finance a portion of the upfront expense. For a typical 2–3 kilowatt residential system, the post-subsidy cost can still run into tens of thousands of rupees.

Commercial banks, however, have shown caution in extending unsecured loans for rooftop solar systems. Lenders cite concerns over repayment reliability, lack of collateral, and limited historical performance data on solar-backed consumer loans.

According to reporting by Reuters, several applicants under the Surya Ghar scheme experienced delays or rejections despite meeting eligibility requirements. Banking officials have reportedly raised concerns over enforceability and default risks in smaller towns and rural regions.

Credit Access in Rural India

The problem is more acute in rural areas, where formal credit penetration remains uneven. Many households lack documented income streams or established credit histories, making them less attractive to traditional lenders.

Energy finance researchers at climate policy think tanks have noted that rooftop solar financing requires customised products. Longer tenures, structured repayment schedules aligned with electricity savings, and partial credit guarantees could reduce risk perceptions among lenders.

Without such mechanisms, even well-designed subsidy programmes may fail to unlock large-scale adoption.

Utilities and the Revenue Dilemma

Cross-Subsidy Pressures

India’s state-run electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs) face their own structural constraints.

In many states, higher-consuming residential and commercial users cross-subsidise low-income and agricultural consumers. When rooftop solar enables these higher-paying customers to reduce grid consumption, utility revenues decline.

Energy economists argue that this creates an inherent conflict. While national renewable targets encourage distributed solar generation, local utilities worry about revenue erosion and cost recovery.

Net-Metering Delays

The government’s net-metering framework allows consumers to export excess power to the grid in exchange for credits. However, industry associations report delays in approval processes in some states.

In certain regions, utilities have introduced caps on system size or revised net-metering rules, citing grid stability concerns. Such measures, while sometimes justified on technical grounds, can slow the rooftop rollout.

Distribution companies contend that grid upgrades and smart metering investments require funding, and widespread rooftop integration increases operational complexity.

Grid Infrastructure: A System Designed for Centralised Power

India’s grid was historically built around large, centralised power plants. Rooftop solar introduces decentralised generation with two-way electricity flows.

Technical Challenges

When households export power during peak sunlight hours, voltage fluctuations can occur in low-voltage networks. Older transformers and distribution lines are not always equipped to manage reverse power flow.

Smart inverters, voltage regulators and real-time monitoring systems can address these challenges. However, deployment of such technologies remains uneven across states.

Grid experts emphasise that without systematic upgrades, rooftop solar penetration may hit technical ceilings in certain localities.

Transmission and Storage Constraints

Beyond distribution networks, broader transmission constraints can also affect renewable integration. While rooftop systems reduce reliance on long-distance transmission, surplus solar power still requires flexible grid balancing.

Battery storage, though expanding, remains expensive at the household level. Without storage integration, rooftop systems depend heavily on net-metering frameworks and grid responsiveness.

Administrative and Procedural Bottlenecks

Apart from financing and grid concerns, procedural inefficiencies also slow adoption. Applicants often navigate multiple layers of approvals involving local DISCOM offices, inspection teams, and subsidy disbursement authorities.

Industry bodies have called for single-window clearance mechanisms and digitised approval platforms to reduce installation timelines. While the government has launched online portals to streamline applications, ground-level implementation varies widely across states.

Urban vs. Rural Disparities

Data from state renewable energy agencies indicate that rooftop solar penetration remains significantly higher in urban areas compared to rural districts. Urban households generally have better access to financing, more reliable grid connections, and higher awareness levels.

In contrast, rural consumers may face limited installer availability, weaker distribution networks, and delayed subsidy reimbursements.

Economic Implications

Rooftop solar offers long-term savings for consumers by reducing electricity bills. Analysts estimate that households can recover installation costs within five to seven years under favourable conditions.

However, high interest rates on loans can extend payback periods, making systems less attractive financially.

For utilities, unmanaged rooftop growth could widen financial deficits. Experts argue that tariff reforms and revised cost-recovery mechanisms are needed to balance distributed generation with utility sustainability.

Policy Responses Under Consideration

Energy policy experts suggest several measures to bridge the gap between vision and implementation:

- Credit Guarantees: Partial risk guarantees to encourage banks to lend.

- Green Financing Lines: Dedicated rooftop solar loan products with lower interest rates.

- Smart Grid Investments: Accelerated rollout of advanced metering and voltage management systems.

- Tariff Reform: Gradual restructuring of cross-subsidy mechanisms to reduce DISCOM resistance.

- Faster Subsidy Disbursement: Timely payment of incentives to maintain consumer confidence.

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has indicated ongoing discussions with financial institutions to expand credit access.

The Broader Renewable Context

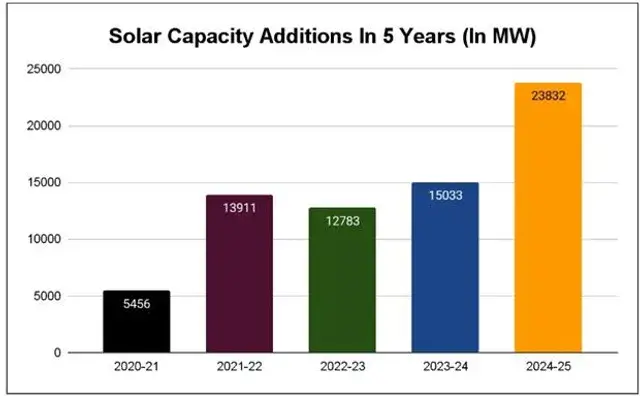

India has achieved rapid growth in utility-scale solar parks, making it one of the world’s largest solar markets. However, rooftop solar remains a smaller share of total installed capacity compared to initial projections.

Energy analysts argue that distributed generation is essential for reducing transmission losses and empowering consumers, but requires coordinated action across ministries, regulators, utilities and banks.

Related Links

Prime Minister Modi’s rooftop solar vision reflects a strategic commitment to decentralised clean energy. Yet translating policy ambition into widespread adoption has exposed structural weaknesses in financing systems, utility business models and grid infrastructure.

Addressing these interconnected challenges will determine whether India’s Modi’s Solar Vision vs. Utility Reality aspirations evolve into a durable transformation or remain constrained by institutional bottlenecks.

The rooftop solar dream is not stalled, but it is slowed. Bridging the gap between vision and utility reality will require financial innovation, infrastructure upgrades and regulatory alignment at both national and state levels.